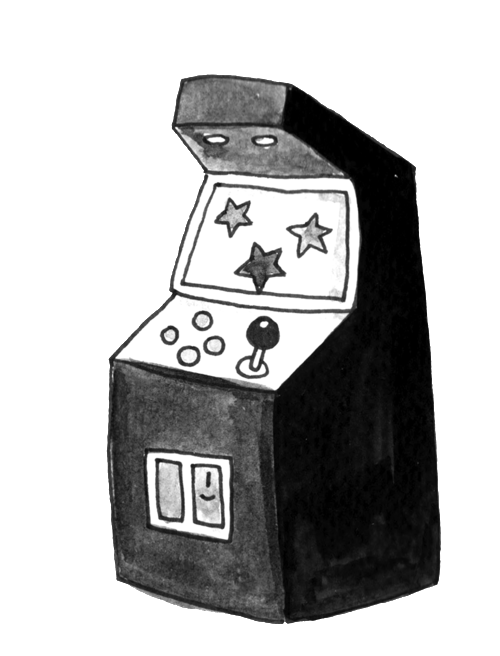

The original Monopoly was conceived by a woman to educate people about the consequences of profit driving development. Hotels became the symbol of this incentive after the game was sold to a toy company.

In 1904, Elizabeth Magie patented The Landlord's Game—an abstraction of 19th century Georgist philosophy that holds economic value derived from land should belong equally to all members of society. Today, the mustachioed, top hat sporting Monopoly Man champions an opposite value system.

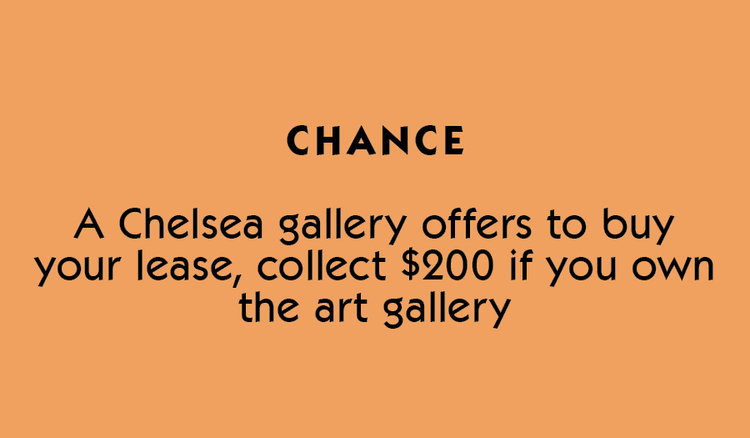

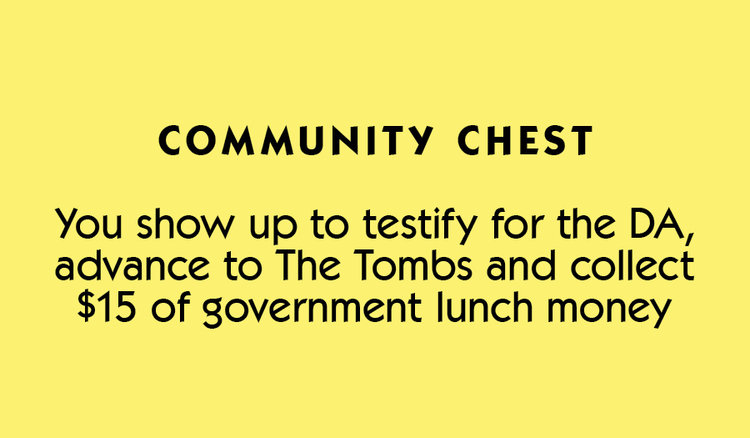

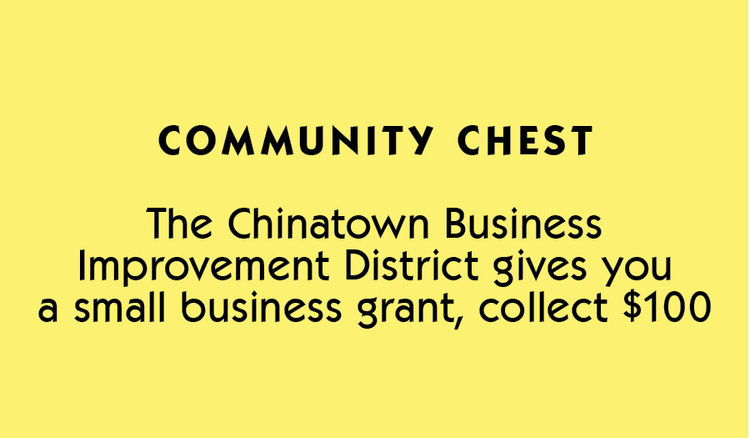

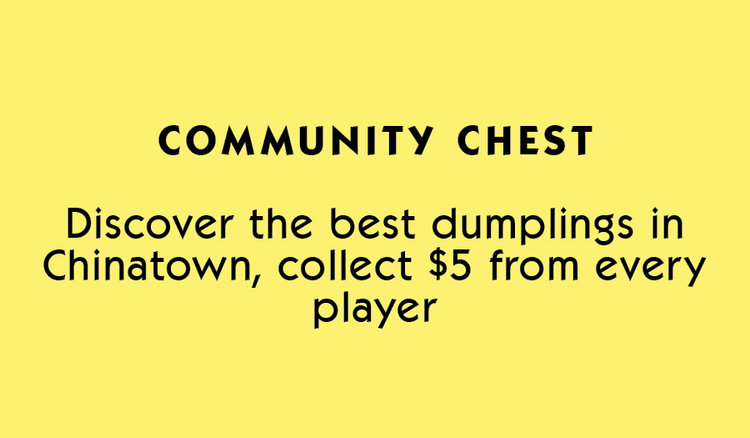

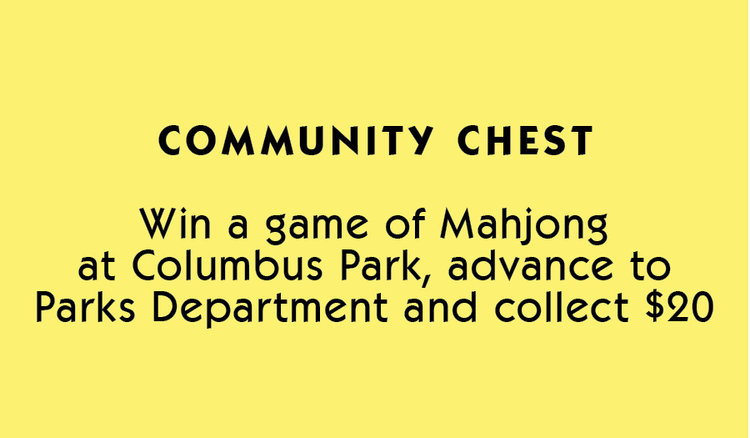

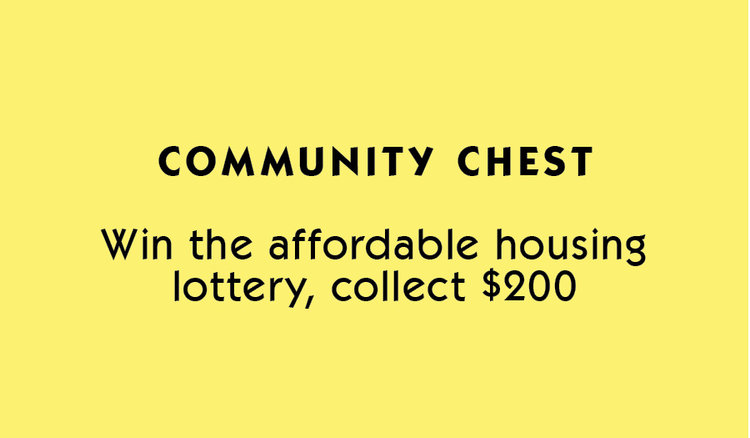

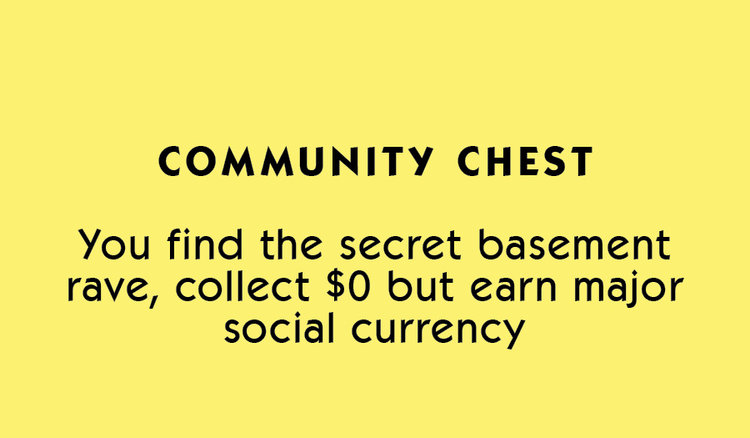

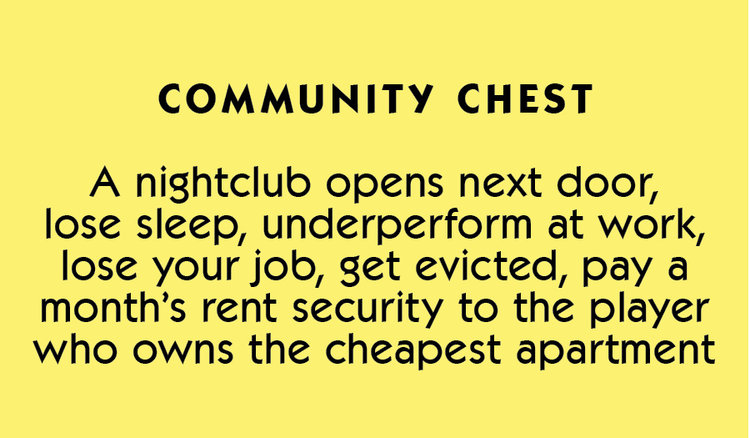

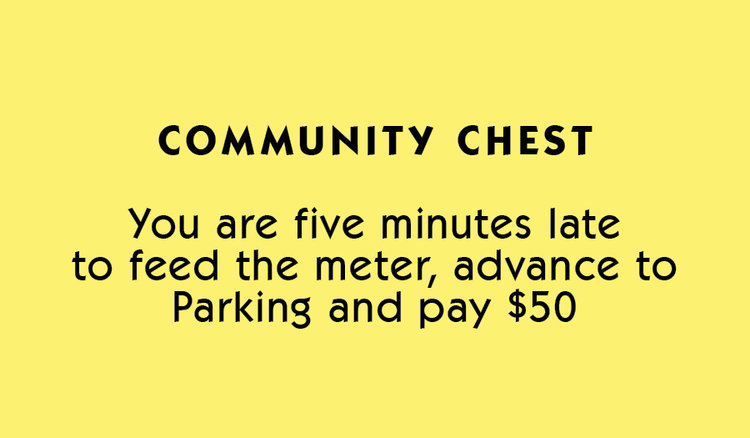

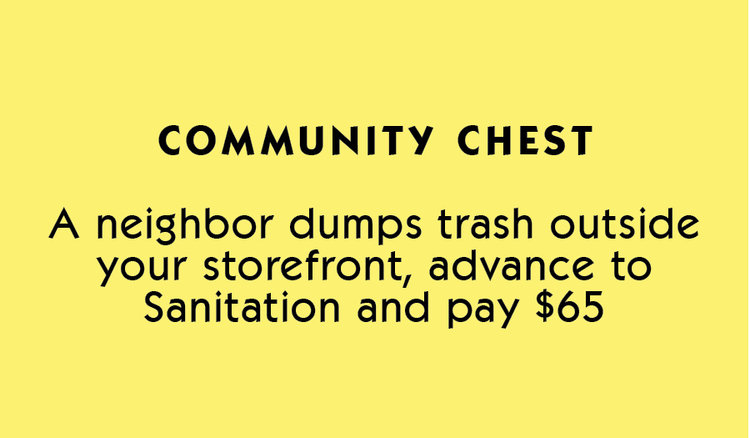

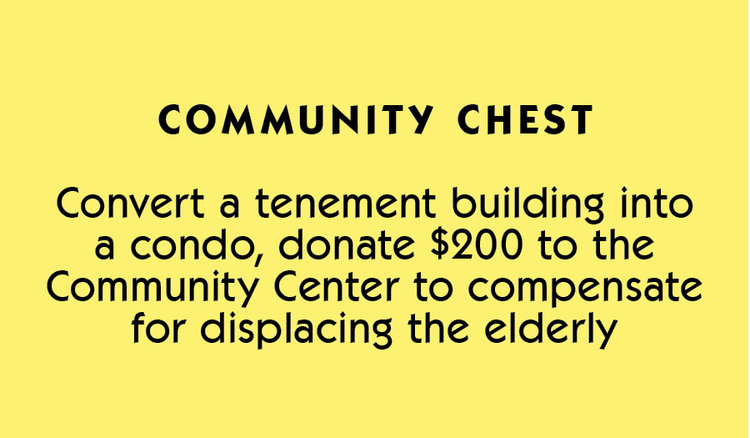

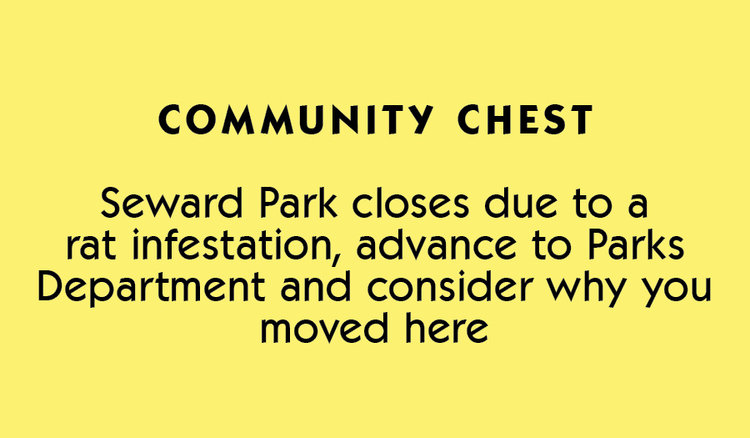

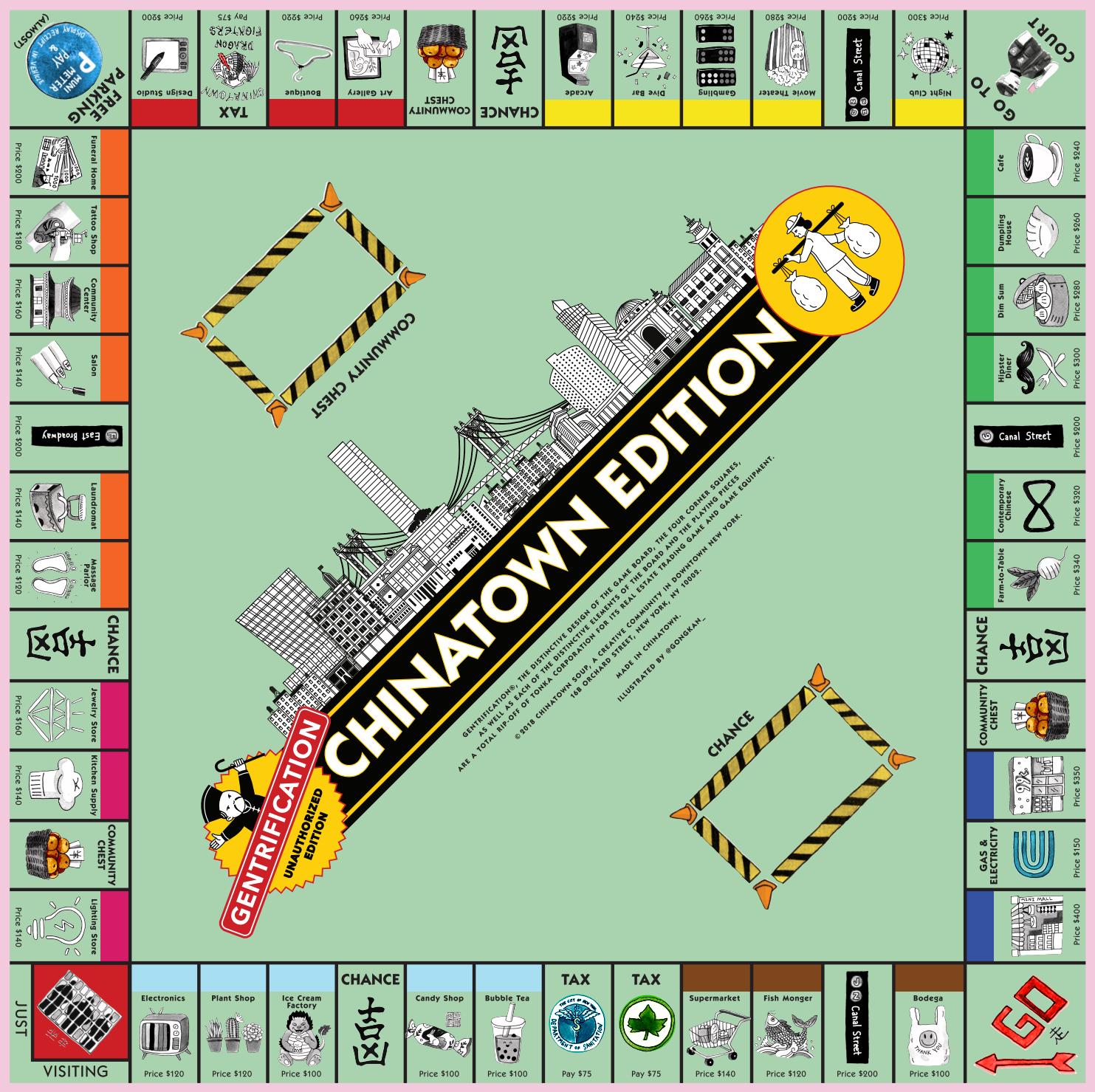

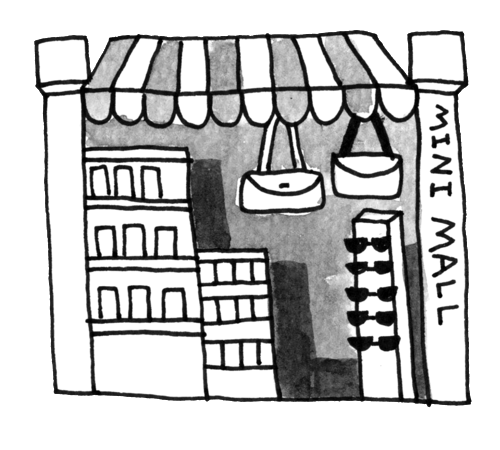

Inspired by recently spotted street flyers featuring the head of Monopoly Man atop King Kong's body straddling what's rumored to be a new hotel development (and channeling Magie's spirit of intent), Chinatown Soup developed a riff on Monopoly that is designed to engage the public in an exploratory conversation about gentrification in New York's Chinatown. Through this project, we seek to activate awareness of how real estate determines culture.

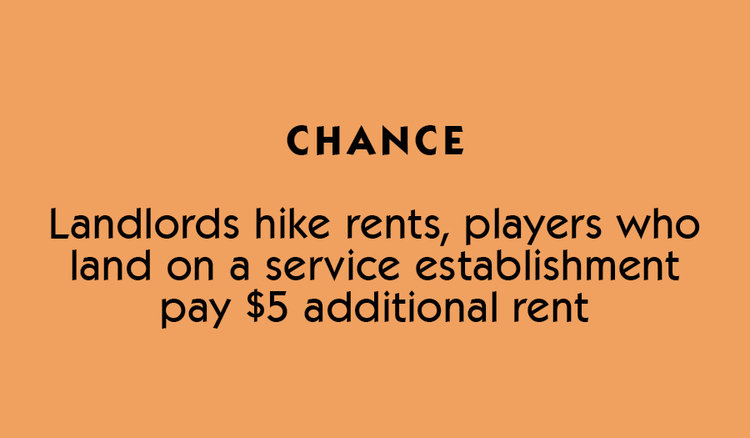

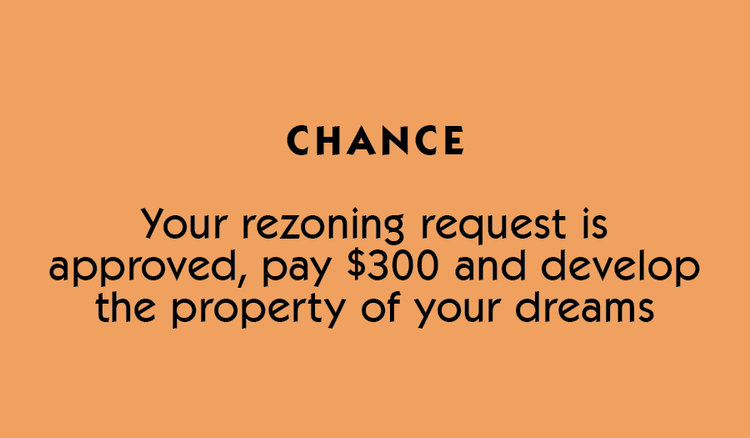

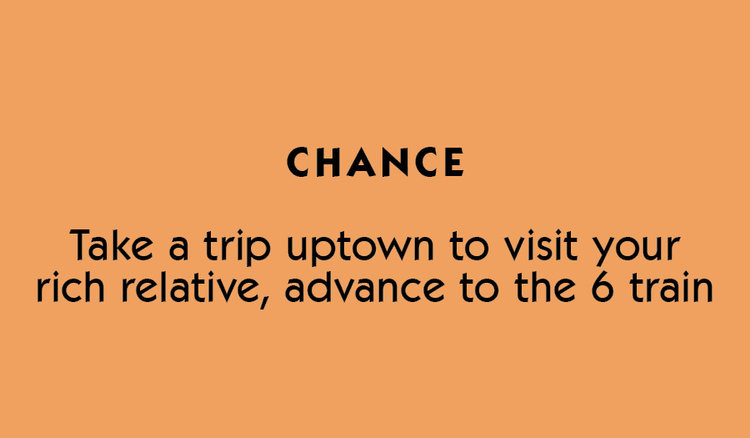

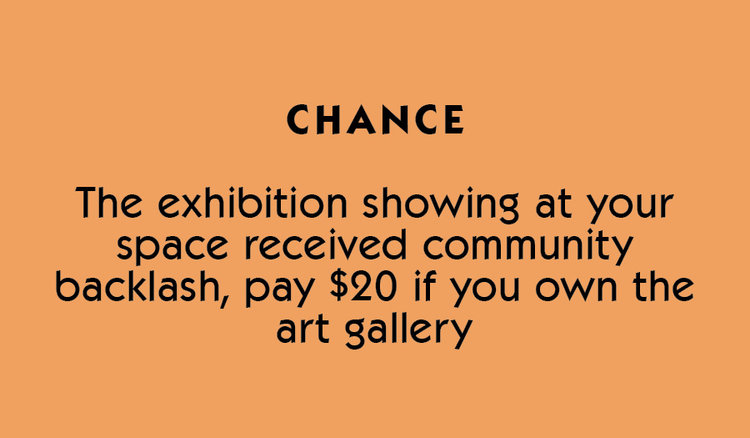

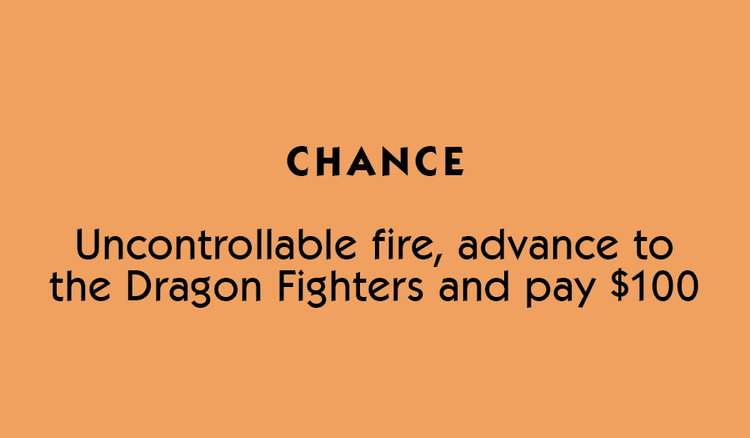

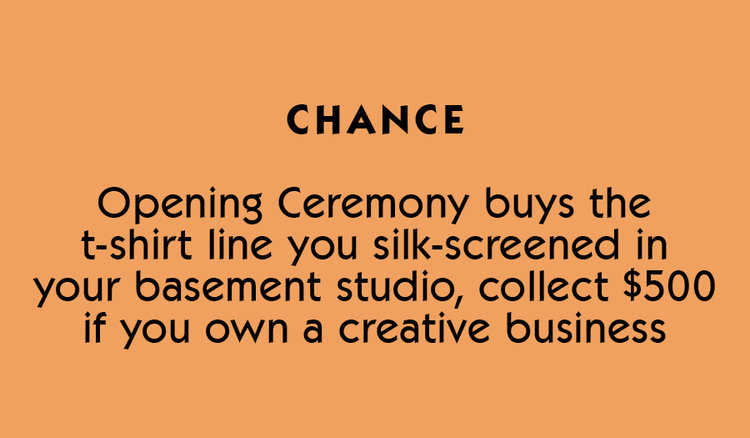

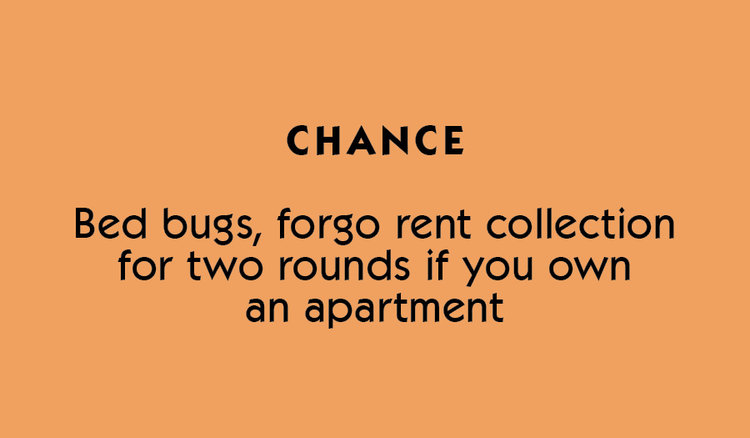

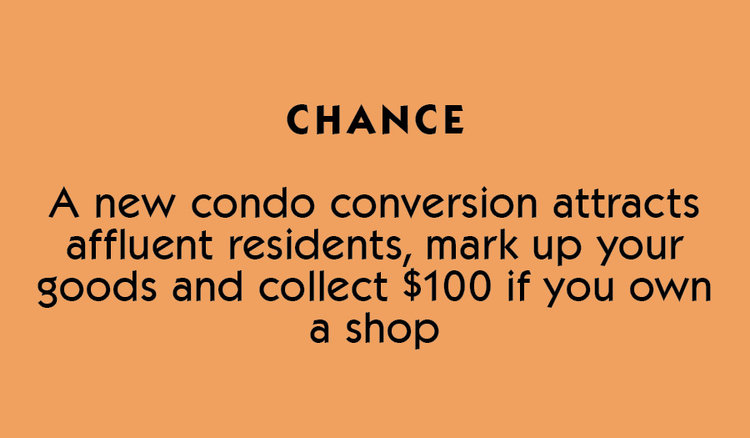

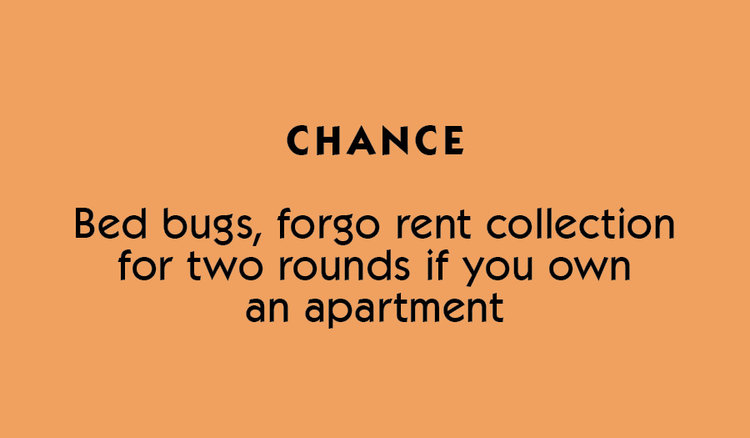

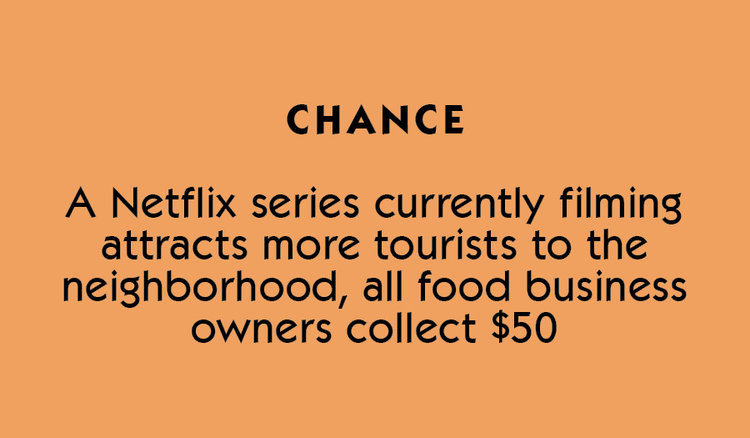

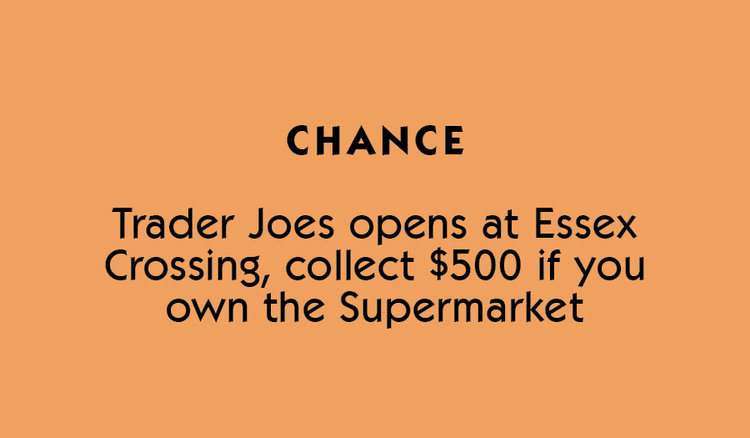

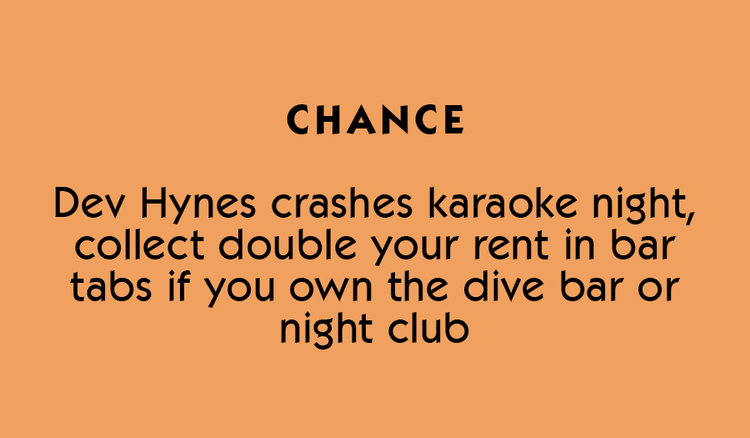

Our board borrows from Monopoly's "New York City Edition" of 1995 for aesthetics. It displays the current business types in Chinatown and invites players to reimagine how trends in commercial and residential occupancy interact.

By complicating the notion of gentrification as simply bad, we hope that people will begin connecting with each other about productive alternatives for how neighborhoods could and should exist.